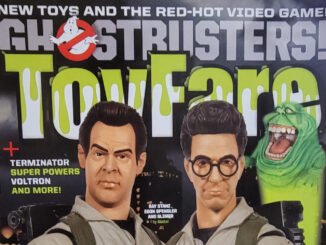

This is the other of the two interviews from ToyFare number 144. Read the other behind-the-scenes interview about Ghostbusters: The Video Game with Drew Haworth here. In this one, we get to hear from the late great Harold Ramis, as he discusses everything from Ghostbusters toys, to the Ghostbusters video games, and sequels, to other projects that he’s worked on.

It’s really fun to go back and read these old interviews, like looking at a time capsule. Especially in light of what we’re about to see in the upcoming Ghostbusters: Afterlife. We hope that you enjoy this look back at the interview that ToyFare conducted with Harold Ramis back in 2009.

The actor/director talks about the new Ghostbusters action figures, video game, and movie, plus today’s comedy in comparison to yesteryear, the upcoming ‘Year One,’ and more!

By TJ Dietsch

Posted 6/11/2009

TOYFARE Q&A: HAROLD RAMIS

Ghostbusters Action Figures

TOYFARE: Have you gotten a look at your action figure yet?

HAROLD RAMIS: I saw the maquette, the clay model of my head, which was cool. Then they showed me a fully dressed figure without the head.

TOYFARE: What was it like seeing an action figure that actually looked like you?

HAROLD RAMIS: It was weird coming after all the toy merchandising that was really predicated on the cartoon show. The movie drove the merchandising and yet they were afraid to use our likenesses because they didn’t know that we would stick with it. So, there was something more generic about the cartoon figures. I have one sitting right here in my office, the blonde Egon. It was cool that we created something that had that much reach into the culture. And now, to see one that actually looks like me and to see our likenesses in the new video game is incredible.

TOYFARE: How long ago did Mattel approach you about the figures and what was your initial reaction?

HAROLD RAMIS: I’m really vague on when the toy stuff started, but it had to be in the last two years. The game stuff probably started three years ago. The game development went apace, but the release of the game was delayed due to the corporate shuffle. The action figures, I can’t remember when we signed off on it, but it’s kind of exciting for me, having spent so much money as a father on action figures.

TOYFARE: Have your kids seen it?

HAROLD RAMIS: Yeah I showed it to them. They’re past it now, they’re 19 and 20 my boys, but I have a grandson who’s seven who will enjoy it. I had a house full of G.I. Joe and Max Steel and Spider-Man and Batman and a lot of Power Rangers.

TOYFARE: Have you seen the figures of the other actors?

HAROLD RAMIS: No, they just showed me mine for approval, both emotional and legal.

Ghostbusters: The Video Game

TOYFARE: What was the process like for working on the video game script?

HAROLD RAMIS: John Melchior came to us and a contract was presented to us a long time ago, saying they wanted to do a video game. John Melchior was the team leader and I met with them and they laid out the vision of how the game would work and it all looked great. The deal was that they would write the script and Danny and I would consult on the script, Danny being Danny Aykroyd. The whole thing just marched along and they presented first an outline, then a more detailed outline, and all the time showing us either drawings or animatics to get the look and feel. Then Dan made some of his comments on paper, I think he added some interesting technological jargon, that kind of invented science that we had so much fun writing in the first Ghostbusters. Then I worked most on Egon’s dialogue as we recorded it and Egon, unfortunately being the scientist, I had enormous blocks of very technical description to do. Very complex instructions.

TOYFARE: Was it fun getting back into that character?

HAROLD RAMIS: Yeah, but the recording sessions were intense because I couldn’t travel to them and, under any circumstances, they wanted to do it as quickly as possible, so the scripts are twice the length of a standard movie script, like 250 pages, a lot of it is just yelling “Look out rookie! Behind you! Throw your stream!” So, a lot of yelling and it’s hard if you’re not a professional stage actor to sustain a voice-over two days with eight-hour days. So Egon might be a little more horse than he was in the films.

TOYFARE: How was it recorded then, if you didn’t go to them?

HAROLD RAMIS: They came to me, they tracked us down. Bill might have recorded in Arizona, maybe Phoenix. I recorded in Chicago, I think Danny recorded in New York and Ernie must have recorded in L.A. is my guess.

TOYFARE: Have you seen any of the guys recently?

HAROLD RAMIS: I talk to Dan a little bit, I’m in touch with Ernie and Bill I have virtually no contact with. I just keep track of him through his brothers who I’m still friends with and other people. You know, he’s a mystery man.

Ghostbusters

TOYFARE: What do you think it is about the Ghostbusters that keep people coming back?

HAROLD RAMIS: Well, you know, to me, “Ghostbusters” worked on a lot of levels. For kids, it was a pure action/supernatural thriller with some really cool tech and some really, fairly cool guys, and decent story. For grownups, it was a satire on all things paranormal, on the kind of guys who would pursue this career. And I think the three of us represented a fairly broad spectrum of attitudes in regard to the supernatural and paranormal. And Sigourney [Weaver] was such an admirable heroine and Rick [Moranis] was such a lovable nerd. It was just really something for everyone.

TOYFARE: How did you get involved with the script?

HAROLD RAMIS: After “Blues Brothers,” John [Belushi] and Dan loved working together so much and Dan is so prolific, he just spun out a lot of first draft film scripts for him and John to play. I think one of them was Spies Like Us. They didn’t get to do any of them because John died so prematurely, but Dan picked up “Ghostbusters” and thought “This should be a movie,” and he brought it to Ivan Reitman who had directed “Meatballs” and “Stripes” at that point and produced “Animal House” and I had worked on all those with Ivan. Dan’s notion was to get Bill Murray involved and to make “Ghostbusters” with him and Bill as two of the Ghostbusters. In their very first meeting Ivan said “We should get Harold to play the third Ghostbuster and you and he can rewrite the script.” And the script was pretty much unmakeable the way Dan conceived it. The Marshmallow Man, which is the large-scale effect that really pays off the whole movie, happened around page 50 in Dan’s original script and things got bigger after that. So, not only was it impractical as a production, it sort of took it too far from the world of the mundane which is where the comic edge was really vivid. Ivan and I had a similar thought independently. We thought the origin story would be really interesting, how the Ghostbusters came to be Ghostbusters, who were these guys, how did this happen, whereas Dan’s original script surpassed all that, he projected into a time in the future when ghost occurrences were common, when Ghostbusters were around pretty much like Orkin exterminators, that there were a bunch of teams around and that the Ghostbusters in Dan’s script were just one of many teams of ghost exterminators in New York. And that was a fantasy premise, but we thought it might be more engaging for the audience to know these guys before they became Ghostbusters and track the origin of their belief, kind of take the audience step by step from a place of skepticism to a place of belief.

TOYFARE: Was there ever a question of where the movie would be set or was it always NYC?

HAROLD RAMIS: Very much so, I think that was a consequence of, well, Bill and I started working in New York in 1974 with National Lampoon. Then those guys ended up on Saturday Night [Live] and I ended up in L.A. writing “Animal House” and then to Toronto doing the Second City TV show, “SCTV.” They became real New Yorkers in those “Saturday Night” years and the “SNL” cast was the toast of the town and they pretty much owned the city and identified with it so strongly. So, that was part of it. Then, it just seemed like the perfect edge for the movie because New Yorkers are so hard to surprise. And playing the supernatural against that setting and there’s no place more gritty and real than New York. So it seemed like playing all that out in New York was perfect and we ended up with the attitude of New York cab drivers. And also, New York is the strangest kind of combination of a big intimidating, impersonal city crossed with a small town where people talk to you out of the blue like they know you. And people are packed so dense that you have to kind of acknowledge everyone and ignore everyone at the same time.

TOYFARE: Was it strange as an actor to be working with all those special effects?

HAROLD RAMIS: You know, it wasn’t really difficult because the whole foundation of acting is pretense, even if an actor is standing there you’re still pretending he is who he is and that he actually means what he says. So you’re always dealing with unreality on one level or another. And, half the time when you see anyone in a close-up they’re acting either to nothing or an actor who’s standing amidst a bunch of light stands and a camera and three technicians and two camera assistants and a director standing behind them. You’re always suspending your own disbelief in a certain way, so it wasn’t that complicated. I’ve kind of jokingly remarked that Ivan Reitman’s two biggest directions during the movie were “Look scared,” and “Look more scared.”

TOYFARE: Was it interesting seeing everything put together on the screen with the effects?

HAROLD RAMIS: We had seen all the graphic material, just not animated, but the first movie was all optical effects and there’s something almost quaint about optical effects now. There’s things drawn on glass or Claymation animations or stop motion or miniatures. There’s a great issue of SFX magazine that has behind-the-scenes on all the “Ghostbusters” special effects and to see a guy in a Marshmallow Man suit walking down miniature Central Park West stepping on miniature remote-controlled taxis is kind of amazing.

TOYFARE: Aside from a few of the Claymation shots, it still holds up visually today.

HAROLD RAMIS: The so-called Terror Dogs, the gargoyle-like creatures at the end, were great when they were on set. Those were guys in large latex suits with TV monitors built into the head so they could see what they were doing and all that was pretty cool. When they had to animate them running across the street into Central Park, the animated figures then never had enough physical weight to look really believable.

TOYFARE: Can you comment on anything regarding the much talked about third Ghostbusters movie?

HAROLD RAMIS: Yeah, I’m just kind of open about it. Dan has kept the torch alive all these years. He even wrote a spec “Ghostbusters 3” maybe four of five years ago and the premise was “the Ghostbusters go to Hell” and I really liked the idea and I consulted with him on his rewrite, but at the time I think it was really a business thing. There was just no way they could bring everyone to the table, not that we were so gluttonous at the time, but they couldn’t put together a deal that made sense for everyone. And as time went by I guess nostalgia and reality set in and we realized that the public really wants a third one and Dan kept beating the drum and kind of dragged everyone to the table and here we are. I’ve just finished “Year One” and the two writers I worked with, the studio really liked them and in fact bought another script from them and they asked me if Gene and Lee, that’s Gene Stupnitsky and Lee Eisenberg, could write a sequel to “Ghostbusters” and I figured “Yeah, why not let them try?” So, where it stands now, I’ve kind of worked with them on hammering out a story, the studio has kind of signed off on our genera premise and outline and the boys, as I call them, are taking a shot at the first draft. We’re very cautious. If it doesn’t look worthy, I don’t think anyone’s going to want to do it and I don’t think any young comedy stars who think they have a future are going to want to be the ones who bury the Ghostbusters franchise [Laughs]. So, it all becomes self-fulfilling, if we want it to happen, it will happen.

TOYFARE: Dan was recently quoted as saying if Ivan can’t direct it, he’d like to see you take the reigns, would you be interested?

HAROLD RAMIS: Well, of course, if it looked great I’d certainly want to consider it. And Dan probably says that out of loyalty, and there’s no one who knows Ghostbusters like me and Dan, [not] even Bill who has a tendency to just show up, glance at the script and go out and be brilliant, Dan and I keep the archive and understand the science and mythology of it all and kind of know the comic edge of it. There are other good people though, I myself think Sam Raimi could do it, he’s both funny and terrific at large effects movies and someone thought for a minute that Judd Apatow was going to do it, there was an internet rumor. I’m sure everyone will get named. I’m sure it won’t be Michael Bay or McG [Laughs] but better to have someone with real comedy chops than someone who just comes from the special effects world.

TOYFARE: Being the keepers of the story, have you ever thought about continuing the Ghostbusters on as a comic?

HAROLD RAMIS: No, I evolved a motto a long time ago that says “Just because you can do something, doesn’t mean you should.” There are too many other ideas that interest me to devote myself entirely to Ghostbusters. I could still be writing “Animal House” comics or the “Caddyshack” TV show or the “Stripes” TV show, all these things have had very long shelf lives, but they’re not new to me. If it was all I had, boy, I’d be right there, I’d be walking around in a Ghostbusters suit like the guys in the second movie at birthday parties, but fortunately, I have other big fish to fry and I want to pursue other things. The idea of getting together with everybody again and delivering something that felt fresh, introducing new Ghostbusters and everything, is mildly appealing.

Year One

TOYFARE: Speaking of new projects, obviously “Year One” is coming out soon, what stage is that at right now?

HAROLD RAMIS: Totally in the can. It’s all promotion and publicity. When we started talking about toys, I started thinking “Hmm, ‘Year One’ action figures…”

TOYFARE: How was it working with and directing some of these younger comedians?

HAROLD RAMIS: I was kind of eased into that world, first by Jake Kasdan when he cast me in “Orange County” and Jack Black was in that film and I actually had scenes with Jack that didn’t make the final cut. Jake is of that generation and he directed “Undeclared” and “Freaks and Geeks” and knows all those guys. He’s since directed other Apatow films like “Walk Hard,” and Jake I knew because I was friends with his parents [“Empire Strikes Back” and “Raiders of the Lost Ark” screenwriter] Larry Kasdan and Meg, and Jake had gone to middle school and summer camp with my daughter and now he’s calling me and sending me the script and casting me in his movie [Laughs] from which I evolved another rule which is “Always be nice to everyone’s kids because they may hire you.” I had a great time working with Jake and Jack and Collin Hanks and Schuyler Fisk, oh and Ben Stiller was in a scene, so hanging out with those guys was sort of the beginning of a connection. Then Judd tracked me down at the Deauville film festival in Normandy, France and he was with Seth Rogen, they were showing “40-Year-Old Virgin” and I was showing “The Ice Harvest” with John Cusack and Billy Bob Thornton and we got along great. I had only known him from his statements in the press and one time when he was interviewed he said, “We’re all the spawn of Harold Ramis” and he had actually tracked me down when he was a teenager doing a radio show about comedy and interviewed me and turned up an old photo of us. So, then, I really liked him and we met again at the Austin film festival where we did a panel together and he actually volunteered to present me with this award thing. So, we were bonding and he asked me to be in “Knocked Up,” so there I was sitting across from Seth [Rogen] who I only knew from a few dinners in France and I really liked his work in “40-Year-Old Virgin.” The Judd connection really sealed the deal and also Gene and Lee had both started as interns and assistants on projects of mine, I’d known them since they just got out of college and they had worked their way up to staff writers on “The Office,” so I was invited to direct some episodes of the office and that also kind of rounded out this connection to that generation and I got along great with Steve Carell, John Krasinski, Jenna Fischer and Rainn Wilson, all the people on that show are great. It really saved me from moving into a generational obscurity that so many people fall into in L.A. where you lose touch with your audience and you can’t get a film made.

TOYFARE: Do any of these younger comedians remind you of the people you came up with?

HAROLD RAMIS: Oh yeah, watching Jack Black work on the set of “Orange County” I actually had a very vivid thought that he had all of John’s strengths without any of his character weaknesses. I told my wife he was like a healthy John Belushi. He had terrific range and, for a big man, he was really light on his feet and he had that great lovable impish quality that so many people like. But John kind of lost it, I think he turned very cynical with his success and couldn’t control his appetites whereas Jack seems very healthy and well-adjusted.

TOYFARE: What differences do you see in comedy today compared to when you were coming up?

HAROLD RAMIS: Well, certain things are eternal and probably go back to classic Greek comedy. I’m sure Aristophanes was making jokes that we’re unwittingly ripping off now. There is something that represents a generational change, people my age came out of first the Cold War and then the ’60s and the ’60s really represented a complete rejection of those kind of middle class, middle American values that the Eisenhower era was so famous for, that kind of Ozzie and Harriet and propriety and the quashing of any kind of left-wing sentiment in politics. There was a strong reaction to that which started off as Beatniks and hipsterism which mutated into a real cultural underground with the hippies and that was politicized through the ’60s with the free speech movement and the civil rights movement and the anti-war movement and then the drug revolution and psychedelic revolution and then the big cultural revolution changed everything. So we were a generation of rebellion and the characters in our early comedies were all rebels. Unlike Woody Allen characters, they weren’t losers, they weren’t nebbishes, they weren’t timid, they were outcasts and alienated but they were empowered, they were self-empowered and those were the characters I think you see in “Animal House” and “Stripes” and “Ghostbusters” and that was a big difference. Now we see a kind of lovable slacker loser struggling to make it and I think that represents a huge social-cultural shift and even a shift in psychology. Young people, for the most part, until Barack Obama, have not been activists for change and that was the spirit that drove our early stuff, a kind of populist thing. And now, it’s much more about the individual trying to make it in a complicated society.

TOYFARE: Do you think tapping into that rebellious spirit is what has given your films such resonance?

HAROLD RAMIS: There are eternal themes that people will always respond to because they describe either the human condition or a common aspiration we all share. It’s what we identify as charisma in other people, the capacity, willingness and courage to stand up and be different, to stand up and speak the truth. Those will always be admirable qualities even when it costs the protagonist something or sets him against authority and everyone responds to that, especially Americans, we love rebels. China is not real happy with its rebels, but we see ourselves as a country founded in rebellion, that’s all about individual liberty, popular or not, it’s not the truth, but we all still have that aspiration. So, there’s that going on and then there’s a longing for justice where bad guys get what they deserve and good guys are rewarded. I kind of honor that. My films are very Hollywood in that sense, there are happy endings in virtually all my films with the exception of “The Ice Harvest” and even there I had to change the ending. It used to end with John Cusack dying arbitrarily and accidentally at the end of the movie. The audience was appalled. It was a great existential moment, but the audience wasn’t buying it. So, I make comedies for people to like them and with films being as expensive as they are, I want people to come [to the theater]. So, to some extent, I indulge people’s need to feel good and hopefully along with it to provide some realistic perspective or present things in a way that’s not dumbed down. There’s an old Second City motto that says “Always work from the top of your intelligence.” I want people to think. I’ve actually heard people leave a theater and say “Gee, when I go to the movies I don’t want to think,” and I almost grabbed the person by the neck and said [Laughs] “What are you talking about? You’re always thinking, whether you like it or not.” It’s an aspiration of mine to make thoughtful and popular comedies.

TOYFARE: What do you want people to think about when they’re leaving the theater after seeing “Year One?”

HAROLD RAMIS: “Year One’s” a real mixed bag. Just from the advertising and a couple images people are saying it’s a caveman movie and it’s not a caveman movie. When the studio asked me what the movie was about when I was first working on it I said “It tracks the psychosomatic social development of civilization through ‘Genesis’.” [Laughs] They said, “We can’t really put that on a poster.” [Laughs] It kind of devolved into “what they didn’t teach you in Sunday school.” For me I was looking at “Genesis” and trying to figure out what it really meant, not in spiritual terms, but what did it describe in the human experience and for that it’s a strange synthesis of developmental biology, anthropology, theology and history. For instance, my interpretation of the Garden of Eden is that it described man in a state of nature, which for me historically meant hunter/gatherer so we’re on the planet for maybe 1500 years before our legendary history begins. So, to me, that’s man in a state of nature and eating from the Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil is the beginning of existential consciousness. So that’s what I depict in the movie. Everything’s fine until Jack eats the fruit and then he gets grandiose. In the Bible it says “Don’t eat from the tree,” and the snake tells Eve “Well, that’s because you’ll be like God if you eat that fruit and God doesn’t want that,” and, in fact, as soon as Jack eats the fruit and for me it’s in any individual’s life it’s where you start growing up. You do the thing you’re not supposed to do and you’re on your own. You broke the big rule, mommy and daddy are mad, they may kick you out of the house and now you’re on your own. It’s when you start making the rules for yourself, now you’re in charge of deciding what’s good and evil and you’ve bought into the whole existential crisis. So, everything in the movie is related to the way the Bible tracks and is also about the development of the individual and also mirrors the development of society. The people they meet are Cain and Able, [members of] an early Iron Age Agrarian society, and it struck me with, literally the second story in the Bible is a murder. It’s like watching “CSI.” They probably had a teaser for the Bible that started with the murder and then backed up a little bit. Murder’s a big story and always has been and it’s not by accident that it’s the second story in the Bible. So I wanted to deal with that. Who are these guys? What is this rivalry? For me, partly, it’s no accident that Able is a herdsman and Cain is a farmer, it’s “the farmers and the cowmen can’t be friends.” [Laughs] It’s a dispute over land use that determined how civilization was going to go. That’s embedded in the picture and the audience doesn’t need to know that, but it’s there.

So, this is more detail than you need, but I basically started reading “Genesis” with a lot of irony.

TOYFARE: Was it difficult directing for all these sets and special effects?

HAROLD RAMIS: The great thing about being the director, as I’ve always said, is that you don’t have to carry anything. You don’t really have to know how to do anything, you just have to be able to express what you’re imagining, lay out your vision for people, and let the people who know how to do things do them. So, I could point our production designer Jeff Sage to different images from Renaissance paintings, actual archeological digs, actual ruins and illustrated Bibles and say “This is the look.” Or other movies. I wanted the Cain and Abel farm hamlet where I play Adam, the father of Cain and Abel, to look like a [Ingmar] Bergman film, like The Virgin Spring. Other scenes I wanted to look like Renaissance paintings. The Garden of Eden I wanted to look like a page from a children’s illustrated Bible. So, once you articulate that vision these incredibly talented people go to work and start producing it. Same with costumes. You just keep trading images. They come to you with whole books of images. “What do you think of this? What do you think of that?” People have described directing as constantly answering questions. “This hat or that hat? This line or that line?”

TOYFARE: You’ve got a lot of guys on the cast known for their improvising skills, did you let them go or did they mainly stick to the script?

HAROLD RAMIS: We encouraged improvising. All of the improvisers I’ve worked with are smart enough to hang on to a good line, when the line really works they will do it. But once you’ve got that down, there’s no reason they shouldn’t keep going or try anything, that’s why we do multiple takes. That’s the way I’ve always worked and how Ivan works and how Judd Apatow really works. It’s part of the deal and everyone expects it. It was a little harder to improvise in this film because, even though the characters have a contemporary consciousness and often express themselves in a contemporary voice, I wanted to filter out anachronism. I didn’t want people referring to things that they couldn’t know or didn’t yet exist in the consciousness. And it’s very subtle, even saying things like “Wait a second,” they didn’t have clock time so there was no sense of seconds and minutes. No one said that in the Bible.

TOYFARE: Did any of those slip through and then got caught later on?

HAROLD RAMIS: Yeah, there were a few. I’m sure there are more than I’m even remembering. But a big one was Isaac the son of Abraham, Abraham is telling Jack and Michael that God gave them all the land basically and described all the borders of Israel. And Isaac said, “Yeah and God just forgot to tell everyone else, we’re having a war with someone every five minutes.” So the line in the movie is now “We have a war with someone every other day.”

Future Plans

TOYFARE: What’s next on your plate?

HAROLD RAMIS: I don’t have anything I’m actively pursuing right now. We read a lot of scripts, I’ve heard a lot of good ideas, but nothing that’s totally moved me yet. It’s such a terrible ordeal directing a film, especially if you take responsibility for script development so I wait until I find something I’m really excited about.

TOYFARE: Are you looking to go back and direct any more TV shows?

HAROLD RAMIS: I signed up to direct another episode of “The Office.” I’ve been asked to direct “30 Rock” and I’m tempted because I like the people so much. But doing these TV shows isn’t wildly profitable for me nor have I ever directed just to direct like a craft guy. But it is fun and if I’m not doing anything else I might just turn up there. I’m looking at some pilot material.

Be the first to comment